What was it about European cultural development that led to the Scientific and Industrial Revolutions, capitalism and environmental destruction? Why didn’t it happen in the apparently much more fertile ground of China, India or the Arab world?

Here at Lowimpact.org we identify our growth-oriented, wealth-concentrating economic system as the source of the destruction of nature on this planet. But how did our economic and political systems develop, if they’re so destructive? Is there something about human psychology that makes our current ecological predicament inevitable? Can it be down to the human mind being influenced by certain cultural norms, and does that make ‘every person a prisoner of the culture one is born into’? Furthermore, what are the roots of those cultural norms, how do cultures differ, and what allows some cultures to dominate others?

Dorian Cavé gives us a fascinating overview in this review of Jeremy Lent’s the Patterning Instinct: A Cultural History of Humanity’s Search for Meaning. Dorian holds a masters from the Paris Institute of Political Science and is embarking on a PhD at the Institute for Leadership and Sustainability. He has extensive knowledge of climate change and sustainability, particularly regarding China. He’s also our specialist advisor on ‘the nature problem’ (scroll down), and you post queries about our ecological predicament there. Over to Dorian:

Through the chaos of conflicting signals and the dizzying maelstrom of information in which our digital minds are plunged day by day, a tenuous, but sustained and increasingly piercing sound can be heard by whoever chooses to listen. It is a chorus of voices repeating the same message in unison: “The human species is busily engineering its self-destruction, and taking much of the living world with it. We are doing this, right now. This planet might not remain habitable much longer.”

But the voices don’t seem to be making much of a difference as far as we can see. Nothing large-scale and meaningful is being done to put an end to economic growth, halt climate breakdown, and prevent the mass extinction of other species. Collapse is in the air.

Surely one can blame entrenched social, political and economic structures for this state of things. But how did these structures rise to dominance in the first place? Could their historical triumph, and the apparent fatality of their persistence, be due to certain deep-seated worldviews? If so, what are the fundamental metaphors that have led mankind to inflict such acute destruction on the biosphere and on itself? And what new ways of thinking must we shift into, collectively, to avoid the worst?

The history of our minds

These are some of the key questions explored by Jeremy Lent in The Patterning Instinct, a carefully referenced opus of rather astonishing intellectual breadth, ten years in the making, which delves into about a dozen different scientific fields, from cognitive science to anthropology to history, politics, and ancient Chinese philosophy. Indeed, its wide-ranging transdisciplinary reach and focus on answering “Big Questions” bring to mind works such as Jared Diamond’s Guns, Germs and Steel, with which it can easily be compared.

These are some of the key questions explored by Jeremy Lent in The Patterning Instinct, a carefully referenced opus of rather astonishing intellectual breadth, ten years in the making, which delves into about a dozen different scientific fields, from cognitive science to anthropology to history, politics, and ancient Chinese philosophy. Indeed, its wide-ranging transdisciplinary reach and focus on answering “Big Questions” bring to mind works such as Jared Diamond’s Guns, Germs and Steel, with which it can easily be compared.

Diamond’s book aimed at understanding why it was Europeans who invaded the Americas and defeated the Aztecs and Incas — and then proceeded to colonise much of the rest of the planet — and not the native Americans, or the Chinese, who launched into a conquest of Europe. Lent, too, is keen on elucidating deep historical trends; however, instead of focusing on the historical importance of environmental (bio-geographical) factors, he looks into the history of our minds.

His central thesis is that “Culture shapes values; and values shape history.” In other words, each society shapes the minds (or cognitive structure) of its individual members in ways that will largely determine our worldview, our approach to morality, or the meaning we give to our existence, thus influencing the destiny of this society. This is accomplished through language, and the use of powerful root metaphors (in the Lakoffian sense) — i.e. symbols so constitutive of our understanding that like the proverbial water to the fish, these structures that affect us so deeply are nonetheless all but invisible to us.

Lent develops this “cultural history” of our minds by first venturing into prehistorical times, and the emergence of homo sapiens’ cognitive abilities before and after the agricultural revolution. He then looks into the different cultural paths followed by various major agrarian civilisations, with particular emphasis on Greece, India, and China. Follows an account of the rise of Judeo-Christian monotheism and of its striking influence over the advent of the scientific revolution. The book closes on a sombre reckoning of our civilisational predicament and what it may lead to, and offers insights into a way out of this mess that draw on systems thinking, an approach with fascinating parallels in ancient Chinese philosophy.

Prehistorical worldviews

In the first part of the book, Lent explores the physiological, anthropological and sociological factors that have made the human brain such a powerful organ. He notably stresses the importance of that specific part of the brain known as the pre-frontal cortex (PFC) in enabling humans to develop symbolic language, at the root of what Lent calls the “cognitive revolution.” It would seem that the growth and expansion of the PFC, which is a feature unique to humans among all primates, was simultaneous to the development of language itself. But apart from boosting our means of communication, the PFC is crucial in enabling us to construct patterns of meaning, i.e. the capacity for abstract thought, by adding a symbolic, metaphorical dimension to our physical existence. 1 This patterning instinct” has made possible increasingly elaborate modes of social organisation — and the belief in a spirit world (“mythic consciousness”), in which all religions are grounded.

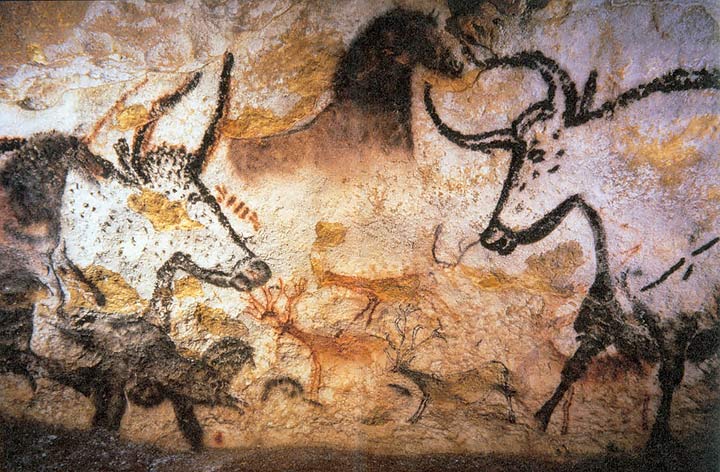

Naturally, symbols and metaphors also paved the way for the emergence of fully-fledged cultures — i.e. patterns of thought that shape the way people construct meaning in the world. This received network of beliefs and values is sculpted neurally into the brain from birth, and reinforced day by day through the symbolic artefacts that are created for other purposes than mere utility (cave art, sculpture, etc.). Such artefacts enable communities to grow massively and complexify while maintaining cohesive frameworks of values and beliefs — while at the same time making every person a prisoner of the culture one is born into.

Splendid metaphors at the Lascaux cave

Lent then presents an outline of how the typical human worldview must have evolved from hunter-gatherer times through to agricultural societies, based on the scant evidence passed down to us from prehistorical times. He points out that hunter-gatherers would have perceived the world as a dynamic, integrated, spirit-animated whole, and as a place of abundance with little notion of private property or boundaries between the human and the spirit world.

On the contrary, the gradual emergence of agriculture must have brought with it an unknown phenomenon: widespread anxiety. Material assets grew more important as food now had to be stored, instead of being readily available in nature, and could be lost or damaged; people had to work hard to grow their crops, which could be stolen from them; and in case of natural catastrophes, one couldn’t just up and leave one’s land that easily any longer. Thus appeared the first boundary lines between humans and nature (the threatening “wilderness”), and between people (with the notion of “home”).

It was at that time that the first religions appeared, based on the worship of hierarchies of gods that had to be propitiated or threatened for the cosmos to keep running smoothly, and for things to be all right. It therefore appears that religion began as an answer to the urge to control and deal with an anxiogenic, threatening outside world. However, this same impulse was embodied in widely different ways among the early civilisations of China, Egypt, Mesopotamia, or of the Aryans: the conquest of Europe by the latter, a strongly male-centered and warlike people who associated power with righteousness, was to have a major influence on history.

Dualism in Greece and India

In the third part of the book, Lent describes how patterns of thought started widely diverging between the people of three major civilisations: Greece, India, and China — with momentous consequences.

The ancient Greeks of the 5th century BC had a peculiar fondness for abstraction. They were the first people to use the definite article as a significant part of their grammar (“the good,” “the beautiful”…) and also devised, for the first time in history, the concept of a pure abstraction: God. They had a tendency to explain everything through a general theory, with a strong emphasis on reaching conclusions through the use of logic and rigorous thought — and, therefore, they came to value the intellect as paramount. In the words of Democritus, “only knowledge acquired through the intellect is legitimate.”

In their eyes, the pure and unchanging language of mathematics reigned supreme. The universe was no chaotic flux but a predictable cosmos, functioning according to rational laws created by a rational mind — and thus, these laws could be discovered by the use of reason. They set about doing just so, developing procedures of empirical investigation along the way that would directly inform the Scientific Revolution many centuries later.

Simultaneously, some of these thinkers — most famously, Plato — developed a comprehensive, dualistic vision of the world, considering the soul as separate from the body, but also as an immortal and unchanging element, and thus, the only part of the human being with access to Truth and the divine realm. And because the soul is the embodiment of the intellect and abstract thought, this led to a deification of reason as the source of what is “good” (and thus, “godly”) in the human experience. In the words of Zeno, “Man’s intellect is God.” This was to become a cornerstone of European thought.

Plato’s Academy: dualism for the happy (idle) few

Indian thought, too, developed a dualistic approach to the universe, which was viewed as ruled by an impersonal and transcendent force. However, it was posited that one could experience Brahman, the core inner experience of consciousness and universal nature of reality, through the interior stillness of meditation — instead of the use of reason. Indeed, only when the both the senses and the intellect are completely stilled, through yogic practice, can one go through the eternal essence within the individual (atman) as the gateway to the infinite and unchanging reality of the universe, and thus escape from reincarnation. The Greeks saw reason, this “uniquely human faculty,” as a link to divinity — and therefore, as the source of a fundamental dichotomy between humans and animals; but in the Vedic tradition, reason is but a tool in the service of true divinity; the rest of the natural world may thus also partake in the divine, with or without the ability of reason. This worldview is the source of the transcendental pantheism of Indian thought, steeped in shamanic “all-connectedness.”

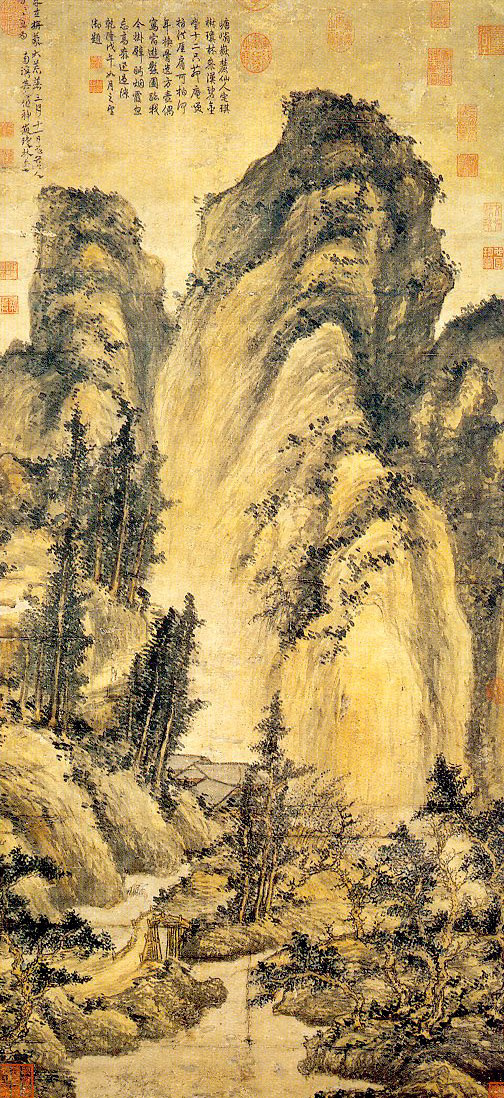

Greece vs. China: essence vs. context

The ancient Chinese worldview is distinctive in lacking a transcendental dimension: indeed, the Tao is everything, and is in everything — neither hidden, nor above. The Chinese root metaphor for the world is that of “The world as a giant organism“: the universe functions based on the harmonious cooperation of all beings, organised into a hierarchy of wholes forming a cosmic pattern. Thus, the aim of the wise is neither to cultivate the intellect (as in Greece) not to arrive at one’s inner truth (as in India), but to learn from nature’s way, and live according to the same harmonious principle. Humans are interconnected with the natural world, not distinct from it; harmony arises from each entity following its own nature spontaneously, just like a cell in the body. This worldview, which leaves no room for the Platonic notion of a soul distinct from the body, is a fundamentally life-affirming philosophy, very much at odds with the Greek view of the human body as a “tomb” in which the soul is temporarily imprisoned.

The ancient Chinese worldview is distinctive in lacking a transcendental dimension: indeed, the Tao is everything, and is in everything — neither hidden, nor above. The Chinese root metaphor for the world is that of “The world as a giant organism“: the universe functions based on the harmonious cooperation of all beings, organised into a hierarchy of wholes forming a cosmic pattern. Thus, the aim of the wise is neither to cultivate the intellect (as in Greece) not to arrive at one’s inner truth (as in India), but to learn from nature’s way, and live according to the same harmonious principle. Humans are interconnected with the natural world, not distinct from it; harmony arises from each entity following its own nature spontaneously, just like a cell in the body. This worldview, which leaves no room for the Platonic notion of a soul distinct from the body, is a fundamentally life-affirming philosophy, very much at odds with the Greek view of the human body as a “tomb” in which the soul is temporarily imprisoned.

Drawing from the work of George Lakoff among others, Lent shows how these fundamental cultural and metaphorical differences have been deeply integrated in the Greek or Chinese languages through a process of mutual reinforcement, leading to a deep persistence of underlying structures of thought across generations.

The greatest contrast between these two cultures stems from where they look for the true nature of reality. As Joseph Needham observes: “Where Western minds asked ‘what essentially is it?’, Chinese minds asked ‘how is it related in its beginnings, functions, and endings with everything else, and how ought we to react to it?” In other words, while Greek minds are engrossed in the abstract dimension of Forms — with a tendency for universalization — the Chinese instead focus on the material world and its intricate inter-relatedness — thus aiming for contextualization.

Besides, the Chinese view is that reality can and should be understood in a holistic way by means of all the capacities of the human being, including reason, but also emotions and intuition; as a result, reason has no inherent value as separate from emotion. And because life’s meaning arises from its context, a defining characteristic of humanity is one’s existence within a social nexus; therefore, while the early Greeks were ultimately “more concerned with knowing in order to understand,” their counterparts in China were “more concerned with knowing in order to behave properly toward other men.” (D. Munro)

The massive impact of Judeo-Christian monotheism

Having established this great dichotomy, Lent then proceeds to retrace a transformative process in the development of European thought: the birth of Judeo-Christian monotheism.

The Hebrew conception of God was radically new in the history of mankind, since it viewed the source of all that is sacred as belonging to a transcendental realm, unreachable for humanity except through the mercy and goodwill of God. In this view, the rest of the universe therefore loses all divinity and is little more than dead matter. Meanwhile, in Greece, Plato and his followers deified pure thought, and saw the union of the rational soul with the eternal world of ideas as the path of salvation for an intellectual elite. In 20 BC, Philo of Alexandria synthesised the Hebrew and the Greek dualistic traditions into a common whole, establishing the Jewish God, in his glorious abstraction up in the heavens, as none other than the ideal Good of Plato. Christianity, which was a direct product of this momentous fusion, then started offering eternal salvation to anyone willing to believe in the power of Christ.

Why was that such an important development? Because the Christian doctrine further entrenched the dualistic divide invented by the Greeks between a pure, immortal soul, and the physical world — including the human body, but also the entire natural world — viewed by Augustine for example as anathema to the purity of God: “Late have I loved thee, O Beauty so ancient and so new…” So deep-rooted was this notion that Descartes himself, while attempting to question everything and base his philosophy on an unshakable foundation, ended up building his ideas on this very dualistic underpinning — neglecting the fact that the constructions of his mind and his sensory experience might both offer valid perspectives on reality. And we do know how pervasive Cartesian structures of thought remain in the modern world. They have come to form the basis for the modern view of our relationship with the natural world: if the mind is the source of true identity, then bodies are just matter of no intrinsic value. And if that is true of our own bodies, it must be equally true of the rest of nature, since neither animals or plants possess a mind capable of reason. Indeed, in the eloquent words of Descartes:

“I do not recognize any difference between the machines made by craftsmen and the various bodies that nature alone composes.”

Descartes therefore completed the process begun by monotheism that eliminated any intrinsic value from the natural world. Nothing is sacred about nature any longer — an assumption never questioned, be it by religious or rationalist thinkers.

Another upsetting child of monotheism was religious intolerance, which heretofore didn’t even exist. Never before the Hebrew Deuteronomy was the concept of a war of ideology ever expressed. The history of Christianity and Islam is replete with the burning of libraries, the suppression of free thought, and religiously motivated mass murder — phenomena virtually absent from the rest of the world, including India and China, even though an initial wave of monotheistic carnage did follow the arrival of Islam in the Indian subcontinent.

On the modern relevance of ancient Chinese thought

Meanwhile, in Song-dynasty China (eleventh century)… a new philosophical current emerged that was to dominate Chinese patterns of thought until the clash with European powers in the 19th century: Neo-Confucianism (宋明理学). In one of the book’s most fascinating chapters, Lent shows how this school of thought, blending elements of Taoism, Buddhism, and Confucianism, arrived at a conception of the universe that is both rich with spiritual meaning, and full of insights into the structure of reality that now resonate astonishingly well with recent findings from systems and complexity science.

On the moral plane, these thinkers saw humanity’s intrinsic connection with the natural world as the ultimate source of value; one should therefore attempt to fully apprehend the coherence and interconnectivity of everything, and investigate things (within and outside oneself) with an attitude of reverence, using one’s entire mind-body organism instead of merely the intellect. Natural emotions shouldn’t be transcended or repressed, but harmonised with the Tao in one’s own nature and the world around. By harmonising and holistically integrating intellectual understanding, ethical engagement and emotional intelligence, anyone can connect with the integrity of the entire natural universe, and thus reach sagehood — i.e. the natural inclination to do good.

Lent quotes the philosopher Zhang Zai’s beautiful “Western Inscription” 2:

“Heaven is my father and earth is my mother, and I, small child, find myself placed intimately between them. What fills the universe I regard as my body; what directs the universe I regard as my nature. All people are my brothers and sisters; all things are my companions.”

乾称父,坤称母。予兹藐焉,乃混然中处。故天地之塞,吾其体。天地之帅,吾其性。民吾同胞,物吾与也。

The Neo-Confucean’s epistemological findings were closely intertwined with this ethical vision. They viewed the entire cosmos, including time, space, or the human consciousness, as being formed by infinitely complex interactions between a structure (or “coherence”) of underlying, organising and connecting patterns (the li 理) — which are universally embedded within larger patterns — and a fundamental energy, indestructible and continually transforming (the qi 氣), which is also embodied within all matter. Thus, energy and matter are organised in coherent fractal patterns, determining every aspect of reality.

This understanding finds striking echoes both in Einstein’s Theory of Relativity (in which energy and matter are transmutable), but also in modern Systems Theory disciplines, which see the natural world as a complex of different systems constantly interacting. These dynamic systems, big and small, all self-organise to create a cohesive whole that cannot be completely understood by reducing the system to its elementary parts. Some neuroscientists use vocabulary close to the Chinese concept of li to speak of consciousness. Other similarities can be found in Phenomenology, which has also studied fractal nestings of consciousness within greater surrounding patterns, and in gestalt psychology, which views human perception as a holistic, self-organised integration of a complex interplay of patterns.

Metaphors and the quest for power

In the following part of the book, the author uses the previous chapters as conceptual building blocks to answer in more detail the million-dollar question: why was it Europeans who launched into a conquest of both the world and nature, and not, say, the Chinese?

Unsurprisingly, he sees the reason for this as rooted mainly in the realm of metaphors — for, according to Lakoff, “New metaphors have the power to create a new reality.” One of these metaphors was that of “Conquering Nature,” expounded by Francis Bacon and others within the Christian context as referring to the process of recovering an absolute form of authority over all living things that was once granted by God (as expressed in the Bible). No less influential was the notion of “Nature as a Machine,” which provided the perfect cosmological foundation for the scientific investigation of the world in the Christian paradigm. This metaphor is still widely used nowadays by the likes of Richard Dawkins, according to whom “a bat is a machine,” and life, “just bytes and bytes and bytes of digital information”; or Ray Kurzweil, who views the mind as “software” in the corporal “hardware.”

Because of these metaphors, the European mindset gradually came to view as completely legitimate, indeed necessary, “truly to command the world” and to open all the secrets of nature “for the purpose of the peace, quiet, and plenty of human life.” But we too easily forget that this view is in fact unique to the Judeo-Christian tradition: nowhere else has nature ever been viewed as created specifically for mankind — especially not by hunter-gatherer societies, who saw nature as a giving parent, or in ancient China, where nature was considered a vast organism that mankind was but a part of. Which doesn’t mean that no environmental degradation was committed on behalf of foragers or the ancient Chinese; but never did this take place to the systematic extent that became the norm in Europe, where a new conception of power made possible a new degree of exploitation — of both nature, and other peoples.

In the early 15th century, China was vastly superior to Europe technologically, culturally and intellectually. In 1405, Admiral Zheng He started a series of seven long voyages all the way to India, the Arabic peninsula, and Africa, at the head of a fleet of thousands of ships, much greater and more sophisticated than anything the Europeans could build. But his voyages did not aim at conquest or enslavement: on the contrary, besides collecting various curios to offer the emperor, Zheng helped establish embassies for several nations in the Chinese capital.

Chinese admiral Zheng He still has many fans in South-East Asia. It might be hard to say the same about Columbus in the Caribbean.

In 1492, Columbus crossed the Atlantic with three rather shoddy boats. Upon being welcomed as an honoured guest by extremely generous Arawak people in the Caribbean, his first reaction was basically: “These people are meek. They would make good slaves.” And so they were enslaved and massacred.

This comparison is quite illustrative of the very different ways China and Europe had to consider knowledge and technology. Europeans have proved themselves much more ready to use these as means to gain power over their environment — both nature, and other people. For example, the invention of stirrups and gunpowder had a negligible impact in China, but a massive effect on European military might: these technologies were immediately put to use to fight and dominate adversaries, and acquire power, viewed as an end in itself. In China, however, military solutions were viewed as a solution to instability, in order to regain a balance between Heaven and Earth. (or at least, so went the official explanations) 3

The mindset of the Europeans, structured by religious absolutism, a sense of dominion over the natural world, and a mission to conquer nature, shaped their attitude toward their voyages. Be it in Asia or the Americas, treachery was never out of the question, and God was the paramount justification for any massacre. This, compounded later by notions of racial destiny, made the exploitation of all lands, peoples and resources as theologically justified, and even a moral obligation.

The “inevitable” scientific revolution?

Why did the Scientific Revolution happen in sixteenth-century Europe, and not anywhere else? The 9th-century Arabs, whose splendid civilisation was centred in Baghdad, developed systematic investigations in all fields of knowledge, including mathematics and astronomy, and seem to have come close enough to a knowledge revolution; but the advocates of natural science were eventually declared heretics by the religious thinkers, as their findings could distract from the pure truth of religious scriptures. As for 14th-century China, it was so advanced in the industrial, economic and intellectual fields that it was probably at the threshold of a full-fledged scientific-industrial revolution. But it didn’t happen.

The ninth-century Arab faylasufs: inches away from a scientific revolution?

Why not? Perhaps because the Chinese didn’t really see this as something particularly desirable. In the eloquent words of historian Nathan Sivin:

“We usually assume that the Scientific Revolution is what everybody ought to have had. But it is not at all clear that scientific theory and practice of a characteristically modern kind were what other societies yearned for before they became, in recent times, an urgent matter of survival amidst violent change.”

It seems likely that asking why other civilisations didn’t “get there” is merely the reflection of a typically European cultural bias.

To the Chinese, it made no sense to seek fixed laws of nature, because everything is in a state of dynamic flow; nor to develop universal theories from pure logic, because nothing exists in an isolated, theoretical form. And while they considered the use of technology acceptable, “conquering nature” was simply unthinkable. According to Lent, this cognitive structure granted the Chinese civilisation an enormous resilience, manifested through a political and cultural stability without parallel in the world from the Tang dynasty to the 20th century, in spite of Mongol invasions, opium wars, and many a peasant uprising. As Joseph Needham points out, China “has been self-regulating, like a living organism in slowly changing equilibrium.”

Jeremy Lent’s hypothesis is therefore that the main cause the Scientific Revolution happened in Europe is cognitive, rather than geopolitical or environmental, and comes from the conceptual structures shaping European patterns of thought. His reasoning does strike me as quite convincing — especially as he goes on to analyse the development of scientific cognition in Europe, as based in the monotheistic paradigm.

Science, religion, and the tyranny of maths

Indeed, while science is often depicted as pitted against religious faith, pivotal religious thinkers such as Augustine actually gave their blessing to the use of reason, and of the many theories regarding universal truths developed by the ancient Greeks, in order to understand God — although faith remained paramount. Thinkers in the medieval universities of Paris or Oxford began to synthesise classical learning with theology, laying the cognitive foundation of modern science. According to the cosmological narrative of “Christian rationalism:”

– God created the universe according to a fixed set of Natural Laws.

– God gave Man Reason in his image; therefore, it is incumbent on Man to use it well.

– God’s Natural Laws are based on Logic; therefore, Reason can be used to understand them.

– By using Reason to understand God’s Natural Laws, Man can perceive the Truth.

– By perceiving the Truth through Reason, Man can arrive at a glimpse of God’s Mind.

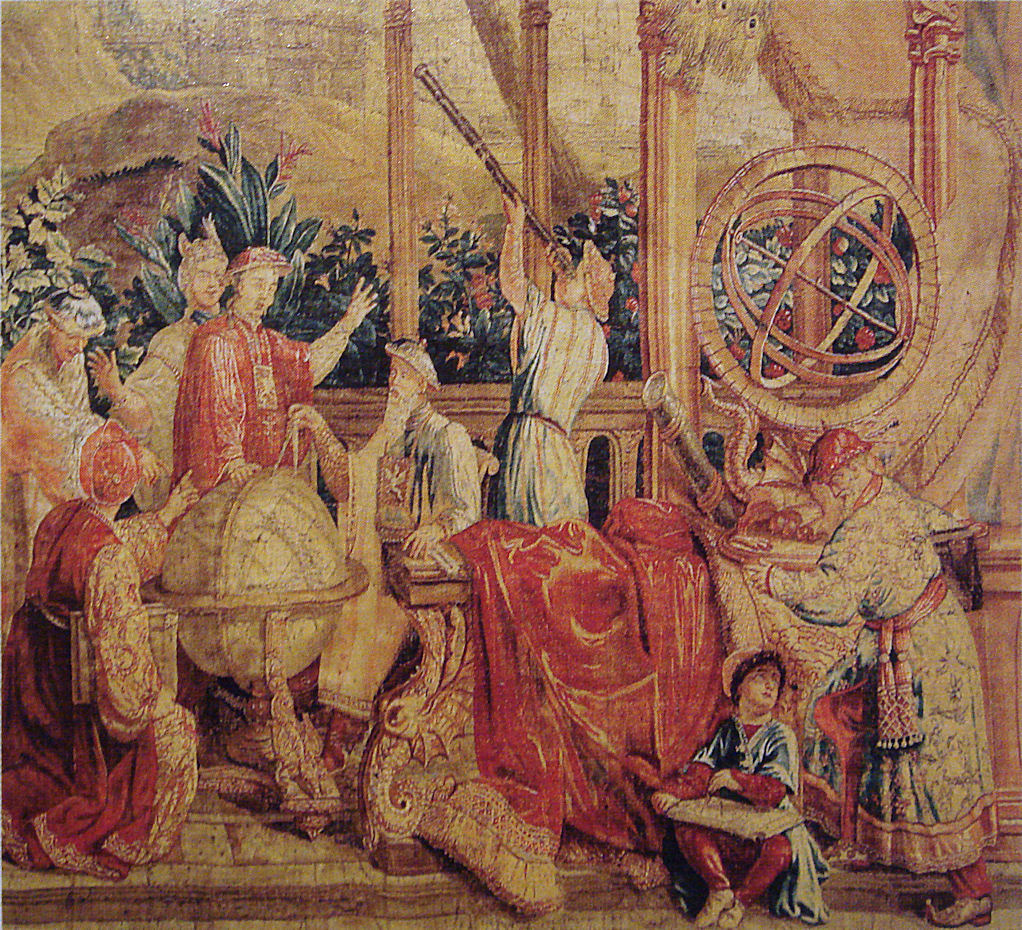

Aquinas stressed that through the empirical knowledge of God’s eternal law as manifested in the natural world, and by using reason, mankind could gain a glimpse of God Himself. Thus, contrary to the religious thinkers in the 9th-century Arab world, the Catholic church actually came to tolerate, if not encourage, scientific investigations, which truly flourished at the time of the Renaissance. Newton himself viewed his “Laws of Nature” as evidence of God’s handiwork; and scientific findings soon came to be perceived as God’s eternal truth revealed to the Christians — and therefore, as an instrument which could be used to try and impress other people (like the Jesuits attempted in China, bringing all sorts of fancy inventions with them as they tried to convert the emperor and his court. They failed miserably).

Converting the Emperor using astronomy. Epic fail.

One persistent cultural assumption that has been passed down to us through the ages, from the ancient Greeks to the Renaissance thinkers, is the Platonic vision of an eternal truth waiting to be “discovered” through mathematics. In fact, the discovered “laws” are often only true in certain circumstances (for instance, Einstein proved that Newton’s laws are not systematically true). Besides, some fields are resistant to the mathematic approach — in particular, those of self-organised complexity, and the non-linear behaviours of living systems, including the human civilisation. Therefore, maths may just be one language among others, and alternative ways of understanding the world may be equally valid, for instance… the systems worldview.

Lent next presents an overview of what he terms “Europe’s moonlight tradition” of thought, closer in its principles to ancient Chinese concepts, which eventually led to the development of systems thinking in Europe and the US in the 20th century. Systems theory views patterns and interconnectedness as fundamental characteristics of reality, and tends to eschew the soul/body dualism. It complements rational reductionism by enabling the analysis of self-organised systems, in particular “autopoietic” living systems that draw their stability from their state of constant flux. In this vision, the whole cannot be reduced to the constitutive parts, as it emerges organically from the complex interactions thereof — in the same way that it makes little sense to describe the works of Shakespeare as “various arrangements of 26 letters”: in complex systems, the patterns that connect the parts frequently contain far more valuable information than the parts themselves. Lent, citing Fritjof Capra (who penned the foreword to his book), therefore views systems thinking as enabling us to experience anew our connectedness with the entire web of life — and the gateway to perceiving nature neither as a machine or a domain to be conquered, but as a “Web of Meaning” connecting all life together.

Collapse, techno-split… or great transformation?

Of course, we are collectively far from this state of mind. As he retraces the rise of consumerism and corporations following the industrial revolution, and up to the appalling social and environmental crisis that we are currently experiencing worldwide, the author attempts a forecast. In his view, our global civilisation — as a complex system — is approaching a “critical transition”. If we stick to our current values and system, we will either experience:

- Collapse. Lent envisions this as a scenario in which, “following the worst holocaust in human history, the survivors will be locked forever in the values and norms of traditional agrarian society, with humans and animals forever exploited as the primary energy source for an elite minority.” He explains this based on the great difficulty of “rebooting” an industrial civilisation, after the low-hanging fruit of plentiful fossil fuels have all been picked. (see this paper for more discussion on this topic)

- Techno-Split. In this other catastrophic scenario, the current economic system manages to struggle on. However, due to ever-increasing inequalities, systematically concentrating always more powerful wealth and technological capacity into the hands of an ever-smaller number of people, the human species will eventually diverge into the genetically-enhanced, techno-powered “happy few” — and the rest, surviving in a wasteland world of toxic geoengineering and absent wilderness.

Both (depressing) scenarios seem quite plausible. However, it would have been interesting to know how Lent came to select just those two, when futurists are equally (if not more) concerned about many other greatly disruptive perspectives.

To avoid either of these gloomy possibilities, Lent calls for a Great Transformation: a worldwide, fundamental revolution in values, based on the recognition of omnipresent interconnectedness. According to him, we must precipitate the collapse of the current global cognitive system before the collapse of the economic and political one, and enable the emergence of a mindset valuing the quality of life over economic performance, and the notions of shared humanity and environmental flourishing as foundations for all political, social and economic choices — i.e. to move away from the metaphor of “Conquering Nature” to that of “Nature as Web of Meaning.” To this end, he cites a study pointing out that “no campaign failed once it achieved the active and sustained participation of just 3.5 percent of a given population…”. Is 3.5% all it takes?!

Intriguingly, or not (given the already considerable scope of the book), Lent doesn’t delve into the specific economic system that might embody this shift of consciousness, and he carefully avoids calling for the downfall of capitalism. But it is certainly difficult to imagine capitalism remaining in place if such a “shift of consciousness” were to take place. As reasons to be hopeful, he mentions the movement that led to the abolition of slavery, and the high proportion of so-called “cultural creatives” in Western countries and worldwide. But is this really enough to be optimistic?

At any rate, considering the situation we are in, I find it hard not to agree with Lent on the necessity of such a shift. Given the high likeliness of horrible scenarios such as the ones he mentions (or worse) unfolding during the 21st century, could any human endeavour be more worthy of an attempt than to bring about this cognitive shift? In that case, where do we start?

Notes

- Interesting resonance here with the Connectivist approach to learning, according to which a person learns by “instantiating patterns of connectivity in the brain“: we can say we know that big cat is a tiger when we recognise the distinctive characteristics of a tiger.

- As Lent points out, we find an echo of this in Albert Einstein’s words: “A human being is part of a whole, called by us ‘the Universe’, a part limited in time and space. He experiences himself, his thoughts and feelings, as something separated from the rest—a kind of optical delusion of his consciousness. This delusion is a kind of prison for us, restricting us to our personal desires and to affection for a few persons nearest us. Our task must be to free ourselves from this prison by widening our circles of compassion to embrace all living creatures and the whole of nature in its beauty.”

- Nowadays, the quest for a “harmonious society” remains a centrepiece of Chinese official-speak, and the pretext for cracking down on all dissent. When content is deleted from the Chinese internet, it is popularly said to have been “harmonised“.

20 Comments

That’s a really fascinating read. It included some things that I’d known, but never realised the importance of – for example that Judaism was the first religion to suggest a transcendent realm and to put God off the planet; and that Philo of Alexandria synthesised that view with the world of forms of Plato, just at the time that Christianity was offering anyone access to that transcendent realm by accepting Jesus as their saviour. Good timing for Christianity.

When it comes to science, are you saying that the Western approach to science – i.e. that nature is mechanical, and there to be conquered by humans – is the problem rather than scientific enquiry per se? In other words, you’re not saying that it’s better not to know things?

And your last sentence – where do we start? I think it’s already started – i.e. a new economy is already being built (community energy, mutual credit schemes, housing co-ops, community-supported agriculture etc. – https://www.lowimpact.org/lowimpact-topic/low-impact-economy/), and our task is to attract people to it, to increase its market share.

Hi Dave,

Yes, I too was quite struck at the discovery of how Christianity can be seen as a product of Judaist and Platonic metaphysics! And while it’s always very easy to indulge in a game of historical “what ifs”, I cannot help but wonder what the world would be like today, had Emperor Constantine never helped promote Christianity in the Roman empire. If Europe had remained pagan and polytheistic, would we have known the Scientific Revolution? According to Lent, probably not.

Regarding science, as I think Jeremy Lent himself told Douglas Rushkoff (who interviewed him for an episode of the Team Human podcast – https://teamhuman.fm/episodes/ep-81-jeremy-lent-the-patterning-instinct/), the book doesn’t lay the blame on the drive to “know things.”

However, there can be different ways to answer this drive. Philosophers in 11th-century China (the Neo-Confuceans), for instance, developed a systematic approach in understanding the cosmos; but their approach was radically different from that of Cartesian European thinkers:

1. Their intention was not to take control of nature, but to discover the ethical principles arising from an understanding of it. It was an investigation into values rather than mechanics: how to live ethically given how the universe is structured?

2. They carried out their investigations without laying paramount stress to the powers of reason and the intellect. Because contrary to Europeans, it would have never occurred to them that logic and abstraction had anything godly or superior. Instead, they held that understanding must be *embodied* rather than just purely intellectual — and that one should learn using one’s entire mind-body organism (xin 心), not just the mind. The very influential thinker Wang Yangming (https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/wang-yangming), for example, stressed that one should always harmonise and holistically integrate intellectual understanding, ethical engagement, and emotional intelligence.

Now, while the ancient Chinese did reach truly remarkable heights in terms of cultural, economic, and industrial development, their thinkers never systematised their investigations like the Europeans did — and therefore, it is notoriously tricky to even consider “holistic” disciplines such as traditional Chinese medicine within a scientific framework. So, does that mean that the method of scientific enquiry really had to be born within the European mindset of “nature as a machine” / “as a thing to be conquered”? I have no idea. But the fact is that historically, it seems to have only ever been midwifed in this context.

(Of course, many brilliant scientists, especially systems thinking theorists, have showed that you can have a rigorous approach to science while embracing a non-mechanistic and non-utilitarian view of life)

As for my last sentence — you are completely right, a new economy is definitely necessary, immediately. But I was referring more specifically to the “Great Transformation” of people’s minds and values that J. Lent calls for at the end of his book… I guess that while new political and economic ways of life are being created and experimented with, simultaneously there needs to be a surge of interest in them on behalf of people who are not already engaged in alternative ways of life. And for this to happen, new values — and perhaps new “stories”, as George Monbiot would have it? https://www.monbiot.com/2017/09/11/how-do-we-get-out-of-this-mess/ — must be embraced massively. So my question boils down to: “How do we create this mental/emotional tipping point?” (Or: “How do we bring at least 3.5% of EVERYONE on board?” 🙂

It’s something I am keen on exploring very actively in the coming years, so if anyone has any good books on this topic to recommend, please go ahead!

I think that’s a contender for most important question in the world, and I’m keen to explore this with you. You’re very welcome to blog with us again if you come up with new ideas / information.

Just looked at the Monbiot article. My pitch for alternative story would be (with explanations where required):

We’re headed for ecological collapse (explain), that will either knock us back to the stone age our make us extinct. Either way, it’s going to cause a lot of suffering and a hugely reduced nature.

The only way to avoid this, or even to slow it down, is to stop chasing economic growth (explain). That rules out not just Neoliberalism, but also Keynesianism, and Soviet- or Chinese-style ‘communism’.

This isn’t possible while the corporate sector has so much political power (explain). We have to reduce their power by building alternatives.

Those alternatives are already being built (explain), and if we can co-ordinate their efforts and increase their market share, it can constitute the beginnings of a new, stable, non-corporate economy – https://www.lowimpact.org/lowimpact-topic/low-impact-economy/.

As far as I can see, it’s our only option. There are no heroes coming to save us in this story. We all have to be heroes, and contribute to building the new economy. And there is plenty we can do – all of us.

Hiya.

I’ve recently come to believe that class based inequalities are at the root of our problems with growth serving the purpose of maintaining these class based inequalities. In particular, I believe it is the middle classes that are seeking to preserve the social mean of middle class consumption and middle class aspirations which are directly leading to ecological and climate breakdown.

This explains why predominately middle class approaches towards inclusivity, wellbeing and prosperity are being utilised rather than Human I=PAT, since the former avoids confronting class inequalities, avoids confronting the social mean of middle class consumption and avoids confronting the fact that society’s aspirations are predominantly focused on middle class consumption levels which are unsustainable in the long term. Eg, George Monbiot refuses to engage with I=PAT but similarly refuses to identify the social aspiration of middle class consumption as being the overriding concern.

This means that the central basis of a Great Transformation is a critical reworking of class based societies and a critical reworking of how class based inequalities drives growth in order to maintain and sustain these inequalities. This means that the real focus of any substantial change is the middle classes with their unsustainable consumption levels and how middle class living has become the social mean of societies.

This line of thinking is a working progress but so far this hypothesis has been able to explain alot, including middle class inertia regarding real on the ground changes. Instead all we are seeing from the middle classes is one talk shop after another. In fact nearly all funding streams are geared towards middle class talk shops.

Similarly, it’s generally the middle classes that want to remain in the growth orientated EU because of the middle class opportunities to maintain class inequalities, despite the fact that the 4 economic freedoms directly damage natural systems in the UK, it’s the middle classes that are behind identitarian politics and the deployment of the ‘race card’ to subjugate the indigenous working classes as inferior and it is the middle classes that predominately controls the narratives about Transition, Transformation, Degrowth or Wellbeing. Presumably so that they don’t have to radically change themselves.

For sure, mutualism is the way forward but if it is the class based inequalities which thrive on competition and predation that is wrecking the natural systems upon which we depend, how is this cultural shift from the norm of inequality and the growth that is required to maintain inequality going to transform into a norm of equality and sufficiency.

In order words, corporate power is predominantly middle class power.

Hi Steve,

I think I see where you’re coming from – you could say that the fear of losing wellbeing and prosperity are what make ideas of “degrowth” so unpalatable to many people, right? And the more you have, the more you’re afraid to lose.

Maybe what needs to be stressed is how consumption levels (and even income), past a certain point, are so utterly disconnected from wellbeing and general happiness. This has been shown over and over again (in Tim Jackson’s “Prosperity Without Growth” report for instance). Consumerism as a nonsensical ideology — which affects all social classes — definitely has to go.

One thing that puzzles me in your comment is why you don’t talk more about the upper-middle or upper classes? It has been shown that the richer a person is, the more impact she tends to have: http://whygreeneconomy.org/information/ecological-footprint-of-the-richest/

Another interesting thing is that it seems that the levels of overconsumption in a certain society are directly linked with the income inequality in that country: https://www.mintpressnews.com/study-link-between-income-inequality-consumerism-size-carbon-footprint/235024/

(the author of this books explains this notably through the “culture of waste” that seems to appear in very socially unequal countries)

For instance, although Japan has a wealthier population (GDP-wise) than, say, the UK, it emits much less CO2 per household. This is of course linked to infrastructure, population density etc. But interestingly, the UK’s top 10% households emit nearly 25 tonnes of CO2 per year, compared to about 15 tonnes per household in the case of the richest Japanese households. Perhaps this means ostentatious consumption is not as big of a thing in Japan – which also had lower income inequality than the UK in 2008: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_countries_by_income_equality

In any case, I do agree with you that social class inequalities drive growth (through status consumption etc.), and that as such, they should be dealt with.

It just seems to me that from the point of view of radical change, this has to be done in a non-repressive, or expropriating way – for fear of triggering more nationalistic, or even “white” (as in “counter-revolutionary”) reactions on behalf of people fearing for their possessions. Instead, maybe there are strategies to harness the progressive role middle classes have often played historically in supporting/bringing about positive social change?

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Progressive_Era

Very thoughtful and engaging discussion of this book – I almost feel like I don’t need to read it (but I will). So, it’ all comes down to messed up metaphors..

Dave:

Your pitch goes straight to the point. I could definitely stand behind this story.

Of course, the main hitch lies in arguing and showing that we can reduce the power of the state-corporate sector through alternatives… And also manage to fend off the attempts, on behalf of this same sector, to stifle or disempower any alternative that starts to grow a little too big.

There is perhaps no other credible way to make this happen than to create a social mass movement around those ideas, so deeply-rooted that

it would become unstoppable…

And the next question is: can this global mass movement be fostered and defended with a minimal recourse to violence? The experience of the ZAD

of Notre-Dame des Landes in France, the fracking protests in Lancashire, or Standing Rock – among countless other examples – are cause for

concern, to say the least. I’ll try to read the book “Why Civil Resistance Works” (cited in the article) for some insights.

In any case, you’re absolutely right – we cannot wait for anyone to save us.

(Have you read this article? https://www.the-trouble.com/content/2018/10/14/what-must-we-do-to-live)

Steve – class is a difficult thing to talk about though, isn’t it? People often start to think in terms of education, accent, clothes etc. – cultural references rather than economic ones. It’s simpler to think in terms of one’s role in the economy, but even then, some will see collecting rent and interest, or shuffling investment portfolios as work. In the end, there are people from whom a portion of the value that they create by their work is extracted to be concentrated in the hands of a minority who do no work. Extracters and extractees – the only true classes, economically speaking. There’s a grey area of facilitators in the middle, and two ways of thinking about how to slow down or eventually stop the extraction – regulation or prevention. Regulation is out of fashion, and prevention encompasses central planning, or the reuniting of capital and labour. Central planning is also out of fashion, and completely undesirable anyway (imho), so let’s help the people who are busy reuniting capital and labour in the mutualist, solidarity, whatever-you-want-to-call-it economy. It may be marginal at the moment, but so was capitalism once. I can’t see a realistic alternative.

Dorian – yes, how do we capture people’s imagination and get a movement going? Would love to talk more about that. I’ll read the article.

If , like me, you found “I=PAT” confusing, see here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/I_%3D_PAT

If we accept that our current problems are driven by millennia old, language embedded cultural mindsets, then surely what we need is some novel synthesis of these approaches that can both contain and transcend them (a parallel perhaps with the achievement of Philo referred to in the piece).

The best candidate for such an approach, it seems to me, is to develop a philosophy of holism that is robust and flexible enough to be the framework for a ‘soup-to-nuts’ cultural myth that addresses and unites all the stories implicit in these older myths, but which can also account for individualism, science and an understanding that life is, inherently, dynamic growth.

This is a big ask! Not to mention that at the same time, we have some increasingly urgent global emergencies. It feels like crunch time for humanity (see ‘The Great Filter’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Great_Filter).

On the plus side, our primary resource is human minds – the only place where any of the values that underpin such a project are known to reside – and we have more than 7 billion of them, and counting. That’s a lot of thinking and valuing power – at the same time as availability of accumulated human knowledge is greater than ever before.

So the fact that ‘Nothing but everything will really do’ (Aldous Huxley, ‘Island’) is daunting, but not necessarily cause for despair.

For me, the work that is missing is not economics, not science, not critiques of power structures (these are all crucial – and I’m focused on economics myself – but you couldn’t call them neglected), but the work that will enable mass cultural engagement with the notion of complexity.

Only this can make possible all sorts of crucial conversations (and from these, new understandings, and from these, new practices) about the inter-relatedness of power and economics, science and nature, individuals and collectives, humanity and the biosphere – conversations which are almost impossible to have with most people at present, because the basic framework of language and concepts is absent. This isn’t because the concepts are abstruse (both religion and economics are highly abstruse, but nevertheless one can have conversations about them with most people – it isn’t that everyone has to be an expert – just that most people accept that the mode of thinking is relevant and important).

People like Fritjof Capra (and now Lent) are in the foothills of this work – attempting to knit complexity science and daoism together. But it seems to me that we need a new synthesis that builds on this work – that presents a new whole, understandable as itself, that looks forwards, not backwards. The late work of Christopher Alexander (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Nature_of_Order) is for me an aspect of such a synthesis – but still insufficient.

Unfortunately, I think that those conversations always have been and always will be (for homo sapiens anyway) impossible to have with most people. Fortunately, it seems (main article) that we only need to have the conversations with 3.5% of the population. If that 3.5% can build something (and they are), then that can attract early adopters / early mainstream (that’s not happening yet), after which, availability and price will bring in the late mainstream, and the laggards will have no option at some point. I don’t think we need to invent anything – all that’s been done. We just have to build it and grab the attention of the potential early adopters. (imho).

Dorian. Thanks for your reply. It seems Danny Dorling has pretty much substantiated that the degree of class inequalities and the wealth disparities that underlay these inequalities has a direct relationship with environmental impact, probably for the reason you suggest – status imperative. Whilst the impact of upper middle and upper classes is an obvious concern when I=PAT is utilised then the impact of the middle classes as opposed to the upper classes becomes greater, simply because there is alot more of the middle class.

I think degrowth becomes denigrated because class based inequalities are usually omitted from that narrative and to expect the working classes to degrow their meagre consumption is obviously unreasonable. It is clearly the middle classes that need to degrow their consumption for maximum effect This means questioning the social mean of the middle class as a reference point for aspirations, status and consumption which at present is clearly unsustainable but as of yet there isn’t a clear articulation of that narrative because in the main it is the middle classes that control the narratives, especially on the left.

In this respect, the working classes have only the right in order to voice their concerns (except for Blue Labour) and so it is hardly surprising that the middle class left deride any idea of national democracy or populism since both these platforms are a direct threat to middle class privileges, middle class EU funding streams, middle class corporates and middle class consumption. Hence their unceasing narrative that leaving the EU will leave the working class poorer but really it is a concern about their own interests.

Therefore, international progressive groupings are largely concerned with middle class interests with the knowledge that the EU is fundamentally a middle class institution that will endeavour to support middle class interests. The unmentionable irony of this middle class progressive internationalism is an EU superpower bloc that is predicated on international realism with the working classes treated as economic pawns in their power battle. In my opinion if anything is going to lead to another world war is the formation of regional superpowers, not the Westphalian system of sovereign states.

I’ll reply again later after work.

Cheers.

Dave. Yes I agree that class is a difficult area to talk about precisely because it directly confronts structural inequalities whereby one person from a lower class is having to work harder than a person from a higher class for the same loaf of bread. It is therefore unsurprising that health inequalities mirror wealth inequalities when a person needs to work less for the same goods or is more easily able to afford quality goods and services. This in turn leads to the cultural framework of value and how different types of work are imagined as more or less important and how this value framework relates to the goods and services that can be purchased as a result of wealth disparities.

This hierarchical value framework obviously flies in the face of Interdependancy and how different types of work are equally important in terms of producing a well functioning organisation. In this respect, I don’t see the Petite bourgeoisie or the Bourgeoisie acknowledging this intrinsic interdependancy anytime soon which in turn will dampen any efforts to create the necessary solidarity in order to build a mass social movement. I say this in reference to the fact that the majority of the owners of the means of production these days are the shareholding middle and upper classes which is why mitigation as opposed to I=PAT is the primary strategy to avert ecological and climate breakdown. A strategy of mitigation enables the status quo to be preserved, as does a focus on wellbeing, inclusive growth and sustainable prosperity. This is the case despite numerous research papers that show that greater wealth equality reduces health inequalities and reduces I=PAT.

I personally don’t see how anything is going to get resolved if the status quo of class based wealth inequalities isn’t confronted. This I think includes solidarity or mutualist strategies unless they are in some way focused on creating greater equalities. Otherwise, structural class based wealth inequalities even within mutualist strategies will tend towards hierarchies that seek to protect these inequalities in some way, usually as I’ve been finding recently when attending meetings on ‘alternative this and alternative that’, the attending middle classes coopt the meeting and then regurgitate existing narratives in order to frame the strategy towards protecting their own interests, i. E internationalism, progressivism, leftism, supranationalism, anti-nationalism, pro-open borders, anti-democratic and liberal. In other words a technocratic corporate state with inadequate mitigation measures but just enough to justify a burgeoning 3rd sector that seeks to mitigate against the impacts of class based wealth inequalities. Hence the huge extent of middle class 3rd sector talking shops which seek to identify problems on behalf of the working classes and then seek to find solutions in such a way as to avoid confronting the inequalities that are causing the problems in the first place.

In short, if the middle classes truly wanted change, despite their altruistic appearances, then change would have already happened by accepting the fact that inequalities damage societal and environmental wellbeing. In this respect, I’m not holding my breath.

Dilgreen. I agree with you that a complex systems approach that can better appreciate the role of interdependancy and move towards polycentric forms of organising and governance would be very helpful. As I understand it, holism has been discredited, not sure by whom, because it does not pay enough attention or give enough power to individual agency. The same can be said of communitarianism which has similarly been discredited because it puts limits on individual liberty. Of course it isn’t the individual liberty or agency of the working classes that is in question but the individual liberty or agency of the middle and upper classes.

This again flies in the face of reason, since by its nature, a closed ecological system will mean limits to consumption, limits to population and limits to affluence. Therefore I presume structural frameworks including functionalism in the early 20th century will be rejected by the middle and upper classes because they invariably highlight structural interdependancy and structural limits to growth. Therefore they will be more comfortable with theories that are based on processes, like agency theory, rational choice theory, enlightened self-interest, liberalism, human rights and any other abstraction that promotes the wellbeing of the individual over and above the wellbeing of the community. Hence internationalism, progressivism, rights theory, all of which seek to avoid or transcend structures, even ecological ones. So for example, it doesn’t matter how many times I say to a middle class liberal Leftie that immigration results in the loss of ecological systems and green infrastructure, it simply does not compute because presumably they cannot comprehend structures, only processes.

In response to the article, this link

https://www.researchgate.net/post/How_can_we_estimate_a_critical_mass_for_a_social_and_economic_change

highlights the complexity and variables of tipping points in particular the willingness of a system to make structural changes. Of course if the 3.5% are in opposition to a greater percentage of people who either wish for a different sort of change or wish to stay with the status quo then that 3.5% are probably going to remain a minority interest.

Another study puts the tipping point at 25%.

https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2018/06/180607141009.htm

Steve – in a solidarity / mutualist / mutual credit system, you don’t get to take value from someone else’s work. Any inequality is down to how much you work, not how many shares you have / how much land you own / how much interest you can collect from lent monies (which can concentrate a proportion of the value of the work of millions of people in the hands of one person). It can’t produce the kinds of inequality ratios that we have now. It can’t concentrate wealth to that degree – certainly not enough to overflow into the political system, to corrupt it.

It’s not really possible to know the percentage required to bring about change – and no figure would make want to throw the towel in anyway. There’s nothing else, as far as I can see.

Dave. I agree, the good fight will always be towards mutualism and greater equality. Note that interspecies (ecological) feeding interactions are generally divided between competition, predation, commensalism and mutualism. Certainty in the US and the UK, the dominant feeding interactions are competition and predation and shifting towards mutualism is an evolutionary if not ecological imperative as highlighted by ‘The Equality Effect, ‘The Spirit Level’ and ‘The Inner Level’.

I think my point is that any mutualist strategy still needs to take account of class based inequalities and the unsustainable social mean of middle class consumption. This means that inequalities must reduce around a reduced social mean of consumption and as of yet I’m unsure how mutualism is going to achieve that without referring to biospherical egalitarianism (https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ecocentrism) by which equality is expanded to include all biotic lifeforms (biocentrism) or expanded to include all natural systems (ecocentrism) https://www.uwosh.edu/facstaff/barnhill/ES-243/glossary

I don’t mean to come across as pessimistic but more realistic and so I feel if mutualism is to work, I feel it must be framed within a bio or ecocentric moral system.

Yes, realism’s good. What I tell people who don’t think that system change is realistic (not you, btw) is that what’s totally unrealistic is continuing the way we are. If they think our current trajectory is realistic, they haven’t understood the implications of climate change or biodiversity loss.