The Small Wind Co-op is a new co-operative, putting up three wind turbines on farms in Scotland and Wales. Anyone from anywhere in the UK can join – we’re offering good returns of 4.5% to 6.5% and even the opportunity to use the electricity generated in your own home. The minimum investment is only £100.

For a really quick (3 minute) introduction, see the video below. Because we are on Crowdfunder, this is our easiest project ever to join – you can buy shares or bonds online and it only take a few minutes.

Community energy has really taken off in the UK over the last few years, giving people the opportunity to directly own green energy generation and bypass the big energy companies, while supporting local communities.

The Small Wind Co-op is a new co-operative set up by the team at Sharenergy – one of the UK’s foremost community energy organisations with over 30 successful projects under our belts, from Somerset to Shetland.

We’re building on that success, offering you the chance to co-own 3 wind turbines as part of a democratic, ethical organisation. You get a decent return on your investment (from 4.5% to 6.5%) and even the chance to use the electricity we generate in your own home. Here are three reasons to join us:

1. A sound investment

You can join our co-op for as little as £100. And you can benefit from a new Government scheme, the Personal Savings Allowance, which means that for many people the projected returns (4.5% for bonds, 6.5% for shares) will also be tax free.

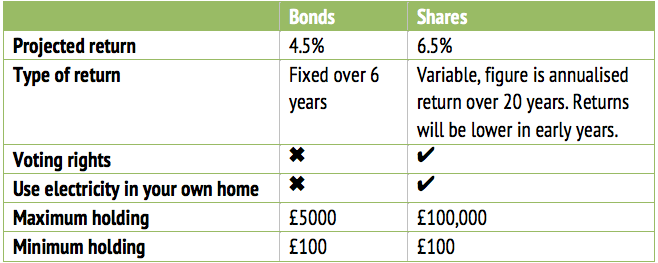

You can buy fixed-rate, fixed-term bonds or long-term shares with voting rights:

2. Your turbines, your energy

Our 3 wind turbines will be in windy spots on 2 small farms in Wales and Scotland, but you can choose to use the electricity generated wherever you are in the UK. It’s like having your own bespoke green tariff – you know exactly where your energy is coming from because you co-own the turbines.

3. Co-operative ethics

Not only are we going to generate clean green electricity, we are a one member-one vote democracy using a proven legal structure. We’ll be contributing to local community funds to help others who live near our turbines, helping local people into employment and supporting community buildings.

For all the details of our project, our sites and our financial projections please see our share offer document.

You can invest via Crowdfunder here.

For more details see our share offer document linked from the Crowdfunder site or on our website www.smallwind.org.uk

Please do pass this on if you know somebody who might be interested. For any questions or suggestions please email us at [email protected] or call us free on 0800 043 4133

13 Comments

Dear Jon,

Will you please explain how you can state that “…you know exactly where your energy is coming from because you co-own the turbines”? This is also repeated in the promotional video.

If these are linked to the grid, which I assume that they are otherwise it would not be cost effective for you without the govt tariffs, then there is no-way that anyone can know where their electricity is coming from. It is a big pool of electrons that travels up and down the country in a fraction of a second.

If it is grid tied, all people are doing is getting an investment return, and actually one which will likely create more greenhouse gases as fossil-fuel baseload back-up must increase to compensate for all these small grid-tied systems.

Andrew

I hope Jon will reply, but as I understand it: of course you can’t buy the specific electrons that were generated by one particular turbine. So you have to link the amount of electricity you take from the grid with an amount of electricity from a particular supplier, and they then get the money for it. Licensing for community energy providers to supply electricity for their local member is so prohibitively expensive that only corporate providers can afford it. Some community renewables groups have got round this and linked up with Co-operative energy who buy their electricity and sell it on to the public, so that people can buy electricity from the co-operative sector and generated by renewables. That’s my take, but hopefully Jon will add to this.

When you say ‘actually one which will likely create more greenhouse gases as fossil-fuel baseload back-up must increase to compensate for all these small grid-tied systems.’ what do you mean? Are you against community renewables?

I am absolutely for community renewables Dave. But only if they are off the main grid on either a local of single system. This is partly because of the extent of grid losses (as described in my book), and hence more waste and greenhouse gas emissions, but also because the “national” grid is just another “marketplace” where most of society is locked into and through which large companies can access income.

I used to be pro- large/large-ish scale wind, as on face value they seem to produce sustainable energy with each turn. But it is not as simple as that. Each kWh generated does not replace a kWh produced from fossil fuels. So, to say that “…you know exactly where your energy is coming from because you co-own the turbines” is, I think, totally misleading, not just scientifically but also misleading to those who want to do what is best for the earth.

The reason is because of wind energy’s intermittency. To stabilise the grid (and when I say grid I mean the national network), there needs to be a reserve able to come quickly online to compensate for fluctuating demand. This is because there is a constant demand (the baseload) and also a fluctuating demand (the peakload) occurring for example at evenings. The more wind turbines that are linked to the national grid, the more need there is for reserve ready to come on a short notice when the wind isn’t blowing. Hence more fossil-fuelled power stations will need to be built, unless some other quick-start large-scale energy source can be deployed. Added to this seeming paradox is the need for fossil-fuelled power stations to run at lower capacities to permit the “green” wind energy to enter the grid. When running below maximum capacity, these fossil-fuel power stations are less efficient and this results in greater greenhouse gas emissions.

I suppose it might be considered better to have small corporations making money from govt renewables tariffs rather than large foreign investors. I don’t think either will help to reduce climate change.

Andrew

Dave has summarised the situation re buying electricity well. You aren’t buying an electron and you’d be pretty disappointed if you did – they actually travel incredibly slowly in electrical wires. You are buying energy. The aim of sourcing green, ethical energy is to know that you are buying energy from a supplier who sources the same amount from a source you approve of. The Small Wind Co-op is not doing anything different from a normal green tariff in this case – except that as a member you co-own the generator so you are in a position to be 100% sure that the claimed generation actually happened. If you don’t like this way of doing things then you more or less have to abandon the grid. I lived off-grid for 10 years and all my power came directly from solar+battery. This is OK, but I’ve come to appreciate the grid – it actually loses very little energy and does a pretty good job of balancing the widely disparate and fluctuating generation and requirements around the UK.

It’s not unusual to hear the claim that wind generation is not as green as claimed because when the wind isn’t blowing we need backup. This would make sense if we were making a new grid from scratch, but ignores the fact that our energy already comes overwhelmingly from fossil fuel sources. So what is actually happening when wind turbines put power into the grid is that less fossil fuel needs to be used up in the generators. You can see this happening on windy days – see http://www.gridwatch.templar.co.uk/ for example.

A more subtle point often quoted in the past was that if fossil fuel generators needed to be ready to fill in the gaps at short notice, they would be less efficient than if they chugged away at a given speed. This is true to an extent, but not really relevant. Firstly, wind is very predictable on a one-hour forecast so that National Grid have plenty of time to react (far more than they get when Andy Murray forces an unexpected fifth set!). Secondly, most fossil fuel generation in the UK is now coming from gas plant which is easier to modulate than coal. And thirdly, the proportion of wind power on the grid needed for this to be a real problem is still a long way off in the UK as a whole – alas.

National grids lose enormous amounts of energy Jon. About 6% of the total generated, and that is a huge amount.

I agree with you both. I’ve never agreed with the point that wind is not so good because it requires fossil fuel or nuclear backup – I prefer Jon’s way of looking at it, which is the exact opposite. We have a grid which is largely fed by fossil fuels and nuclear anyway, and any wind at all that is fed into it will reduce the need for fossil fuels and nuclear. Other renewables that work when the wind isn’t blowing will contribute even more. I’m not really in a position to know which of you is right when it comes to power stations working at less than full capacity.

But I also agree with Andrew about the grid. I know that if everyone had renewables and batteries, then at current levels of technology, the batteries might cause more ecological problems than a fossil-fuel-and-nuclear-fed grid. But what about local, community-owned grids? Better still, local, community-owned grids providing energy entirely from renewables – from community energy, whether wind, solar farms, hydro or even tidal or wave – but also fed by thousands of pv panels on individual roofs. We have solar, but have to put most of it into the national grid for a pittance. Only the big energy companies are benefitting from that.

By the way, I’d love to have a debate with you two about whether the world could be run entirely on renewables, given the current levels of energy use, or whether we’d have to cut use a lot first.

See here for Andrew’s book by the way, for those who are interested – http://lowimpactorg.wpengine.com/books/gasification/.

Imagine being a parent with a number of teenage children. Each night they’ll need picking up from their friend’s houses (or wherever they have been). You can’t make any plans yourself, as they always contact you at short notice, so you sit in your car with the engine ticking over, waiting all evening. Alternatively, to be closer to where they are in case of an emergency, you constantly drive around the neighbourhood which allows you to respond more quickly. You expand your family, or get paid by friends to pick up their children too, so that one car is not enough, which means that you have to buy more cars for your wife/husband/partner to “support” these children. This is grid-tied, distributed wind energy, and these children will never grow up so they’ll need permanent support.

Gas power stations can adjust their outputs and start-up more quickly than coal or nuclear, but it is still not efficient for them to run at “engine ticking over” speed, ready to support wind energy. And the gas plant financiers won’t hold a boardroom meeting each week where the MD says ‘“great news”, XXX have just installed two new wind turbines and so we can reduce our capacity by 0.001% to support them when the wind speed changes’. To make this palatable, everyone who buys grid electricity is compensating these companies by the extra we all pay on our bills. It’s the same “tax” that pays for Drax to import biomass from New Zealand and America, and which attracts investors to install wind energy. This very twisted approach to reducing climate change shifts emissions to other countries and in many ways creates more consumption.

If governments wanted to reduce climate change then they’d ensure that everyone had micro-renewables. There’d be greater independence, less grid losses (ca. 25 TWh annually for Britain), and people would appreciate more the value of energy and decrease use, rather than just flicking a switch and getting whatever power they want. That won’t happen because then there’d be less income for the shareholders of the energy companies. British grid electricity is actually exported because the price is better abroad. It is like the Irish potato famine when people were starving but corn was being sold to England. And, if ever we needed a sign that climate change is not important it is British Gas being allowed to offer customers free weekend electricity as an incentive to switch over to them.

Finally, gas plants are built with shale gas (fracking) in mind, because the reserves of natural gas won’t last long term. Think of this when you consider investing in a grid-tied community wind scheme.

I don’t know what else to say about wind variability really – I can only reiterate that the need for quick backup on the system is caused primarily by the unpredictable variability of electricity demand, not by wind. It may not be the case that energy planners reduce _capacity_ of fossil fuel systems by a tiny amount each time a wind turbine comes on stream – but they do monitor the weather forecast very closely and reduce the amount of _fuel_ being burnt in those generators. And that’s what we want. Power stations don’t cause climate change. Burning stuff in them does.

I can see the appeal of localised, microgrid energy from a ‘small is beautiful’ mindset but it reminds me a little of a Brexit position – standing on our own two feet and all that. We currently have localised distribution systems linked by a high-voltage transmission system linking the whole UK and indeed other neighbouring countries. That transmission system allows us to do one of the best things we can do with renewables – use the fact that it is windy in Scotland to power London. Without that, variability becomes a much larger issue. The transmission part of the system loses only 3-4% overall. That’s way way less than any storage mechanism – batteries, hydrogen, pumped water, you name it.

Micro-renewables also have other drawbacks – small wind has a longer energy payback, and is more expensive overall. Small turbines use a similar amount of land to make much less energy. Small renewables are great but cannot provide all the energy we need in a highly urbanised society. Sure, we could change the pattern of land use over time – I would gladly exchange the twin Mordors of concrete cities and agroindustrial prairie for the Hobbiton of an inhabited, sustainable landscape. But we are nowhere near there, and I don’t think we should let our plan for carbon reduction depend on a very long term societal change.

The idea that wind power is heavily subsidised is pretty much historic. There is effectively no subsidy now available for wind in the UK – ROCs have been withdrawn, Contracts for Difference have been withdrawn, and the tiny Feed-in Tariff allowance is more or less completely used up. Before CfDs were taken away, wind power was bidding to produce power at £78/MWh – that’s a subsidy of around 3p/kWh. That’s much less than is being offered to nuclear – only solar is in the same region in terms of affordable low-carbon generation. Were it not for the effective planning ban on wind in England we would still see wind being built completely without subsidy, albeit in a reduced number of extremely windy sites with low grid connection costs.

There are many problems with the grid right now. As Andrew says, the basis on which energy policy is set is aimed at making some cash for private enterprise, not at reducing carbon. There is huge scope for increasing the efficiency of local grids by using energy efficiently and at sensible times. Access to the grid is expensive, opaque and unfair. But in my view there is every reason to work with the existing infrastructure. Scotland is now at 50% + renewable electricity, using conventional grid – and has massively reduced net carbon emissions from electricity generation. Before recent policy changes, we were more or less on course to join them. Our wind co-ops put generation into the hands of normal people as a small step towards sanity.

Jon,

You’ve obviously made an error when you say that: “….the need for quick backup on the system is caused primarily by the unpredictable variability of electricity demand, not by wind.” Electricity demand goes in regular daily cycles – extremely constant and trackable. Baseload is constant (of course), for things like industrial processes and domestic fridges, and then there are the peakload trends that follow regular increases in the morning and evening. If I knew how to insert a picture on here, I’d show you some wind power outputs in comparison to the regular electricity demand. Wind energy in contrast is extremely intermittent. It is all over the place. The wind farms on the north coast of Scotland for example, where the resource is the best in Europe, often get efficiencies of over 50% which is very close to the maximum theoretical (Betz) limit. Then for consecutive days afterwards they don’t turn at all. This is because the windspeed is fluctuating around 2 m/s and below their cut-in speed. There is no pattern to it: wind is unpredicable and chaotic. And this is the resource that you are saying will power London. What will London do when the wind isn’t blowing? They’ll use the large gas power plants that have to be built as back-up.

When I said transmission losses were about 6% I was being conservative. They aren’t 3 to 4%. Western countries have losses around 7% and some countries like Inda are over 20%. Britian in fact is at 8%. See here: http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/eg.elc.loss.zs. The losses are inherent.

Reducing consumption of electricity is the ideal and actually only sensible approach (onless photosynthesis or water splitting can be made economical). But, as has been said before, this is the elephant in the room. It dare not be spoken of because the economy depends on increasing rather than reducing consumption. My suggestion that microgrids – either single, independent households, or community enterprises (off-grid) are best was because they detach usage from the grid. In doing so they change perceptions of energy use, which is key. Power has to be gathered and is not available ad infinitum at the flick of a switch. Then, obviously there is less wastage, and there aren’t the inherent grid losses, and people manage their power sustainably.

Andrew

I don’t deny that wind is highly variable – I just disagree that the variability of wind is a massive problem, because wind is extremely predictable on the relevant timescale. I am not denying that grids as a whole lose energy – but I see the Transmission system specifically (the backbone) as a boon not a problem. National Grid publish an annual report on Transmission losses – it’s here: http://www2.nationalgrid.com/WorkArea/DownloadAsset.aspx?id=43615. They have not exceeded 2% in the UK as a whole for the last 10 years.

Can wind power London? Wind provides half the overall electricity for Edinburgh, Glasgow, Copenhagen. So why not 50% wind power in London? Let’s not make the perfect the enemy of the good.

In this as in so many other aspects of our attempts to move to a more sustainable and just society, we have a choice between routes. I’m very sympathetic to the idea that we need to become wiser in using what we have. Just chucking more tech at it is what Lloyd Kahn calls ‘smart not wise’ in Shelter and I’m fully aware that applies as much to wind turbines as anything else. I do believe you can get to wise through smart though, and my work on community-owned wind is part of my contribution to that process. It brings people in touch with energy by a different route.

Hopefully this thread will be interesting to anyone who happens on it. I’ll try to avoid posting further – we’ve all got work to do to try to make our chosen solutions work, I guess! Al the best, Jon

Agreed. I was thinking the same myself.

Best wishes,

Andrew

I’d love to try a “free energy generator”like a QEG for example. And … it comes sans smart meter.

In the age of the internet, it’s really difficult not to know that these things are scams. https://www.metabunk.org/debunked-quantum-energy-generator-qeg-10kw-out-for-1kw-in.t3572/. They provide free information to build one, then charge you consultancy fees to put it right when it (obviously) doesn’t work. My advice would be, wait until the inventor gets a Nobel prize for physics, which they definitely would if they invent one that works.