It looks as though heat pumps are going to provide a lot more of our heating in the future – although there has been some controversy about how well they work in old buildings. Heat pump specialist John Cantor answers some of those concerns.

It’s great to see how heat pumps are becoming mainstream, and increasingly the norm for newbuild. However, I have noticed ongoing confusion relating to the use of heat pumps in old buildings. The confusion can start with the ‘will it work’ question. Let’s be clear – the right heat pump could be made to heat any building to any temperature we like. But the crux of the issue is the installation cost and the running cost. The question that we should ask is – ‘can we heat old buildings and achieve acceptable energy-efficiency?’ Well… we probably can, and as time passes, it gets better. Let’s drill into this.

On one level, it is quite simple, but on another level quite complicated.

The simple level relates mainly to the circulating heated water temperature required for poorly-insulated buildings, and this directly affects the energy-efficiency; the Coefficient of Performance (COP) – what heat you get out compared to what electricity you put in. This has implications for the environment and also for running costs.

The complicated level relates to where you want the heat and at what times, and this is all wrapped up with the type of building and its use…. Does it have a lot of internal ‘mass’, brick walls etc i.e. is it slow to heat, and thereafter- slow to cool down. Or is it ‘lightweight’ and mostly insulated internally – quick to heat and quick to cool. Add to this is the occupancy; is it occupied all the time, or empty during the day? Then there are off-peak tariffs and possible future ‘smart grid’ to consider.

Don’t put your hopes too high on finding definite answers here on how best to deploy heat pumps on old buildings for all situations, but you may glean something about where and how heat pumps are likely to be most worthwhile, and also where a good grasp of control settings may be needed.

Heat pumps can promise a fit-and-forget technology, but they sometimes need a modicum of user-engagement if the best results are to be achieved. Maybe more-so in poorly insulated buildings.

The easy stuff

As everyone should know by now, heat pumps are very efficient at producing lukewarm water – It’s an easy ride for them. However, as the water gets hotter, the electrical power-input requirements rise too – the energy-efficiency drops and running cost rises.

The obvious solution to this is to use large-area radiators or well-designed underfloor heating. Both can often provide adequate heat with water temperatures well below ‘hot’. (say 30 to 40°C, 85-105°F) for much of the winter.

Here is the nub of the issue relating to old buildings – it’s more difficult (and a more costly installation) to design a heat-emitter system (radiators or underfloor) to adequately heat an un-insulated building. Especially if using the low water temperatures that energy-efficient heat pumps require. By contrast, well-insulated buildings require far less heat, so should not require overly large radiators. They are the ‘low-hanging fruit’ for heat pumps.

Conventional heating has generally been designed with high-output, for short periods. From plumbers to householders, we are all used to ‘turning the heating on’ and feeling warm fairly quickly. However, heat pumps are far happier operating with lower water temperatures, and this is where some confusion can start. Some patience, and also some confidence in the system is required when setting the required low water temperatures. This is because the system will respond very slowly, and you need to plan ahead and let the building to warm up gently. We are now erring towards a more continuously-enabled system, and contrary to instincts, a heat pump system operated like this can use less energy than one operated on an on/off time clock.

Intermittent heating / constant heating…… starting to get complicated

If the heating is required at a constant temperature, e.g. a retirement home, then things are very easy. The radiators may be able to operate ‘warm’ (not hot) all the time, resulting in very high energy-efficiency (high COP).

Keeping your house warm when you are out is generally seen as wasteful… why heat when you are not there? However, if you do operate with a timer, and allow the house to cool down during the daytime or overnight, then you will need to operate the radiators at an elevated temperature so as to ‘catch-up’, and get the rooms back to a comfortable temperature. The COP will be lower at this time, so you get less heat for your money whist operating ‘timed’. But if timed, you need less total heat due to the lower average temperature of the house. That said, heat is stored in the building’s fabric, so heating while you are out at work is not as wasteful as you may first think.

Both factors (on-all-the-time low, or intermittent and high) can tend to balance out. What you gain on one, you can lose on the other, and vice-versa. The best efficiency is likely to be found with far longer run times than we are traditionally used to. Instead of starting heating 1.5 hours before you get up, try 3 or even as much as 5 hours before, but adjust the circulating water temperature down first (or reduce the heating curve).

The thermal ‘weight’ (or mass) of the building will have a big impact here. If the building is an old brick house (heavy), and a set-back (reduced) temperature is programmed for the night or un-occupied day, then the radiators may need to be considerably warmer to provide comfort in the evenings – not helped by the cold walls. So, in this instance, like the race of the tortoise and the hare, the on-all-the-time tortoise can have the edge due to the good COP resulting from the constantly-enabled lukewarm radiators.

On the other hand, if the building has a lot of internal insulation, and few stone/brick inner walls, it will be thermally ‘light’. In this case the ‘catch-up’ to re-heat to a comfortable temperature should be acceptably short, so an amount of night set-back (lower room temperature at night). is likely to be advantageous.

Unfortunately, I don’t have data or evidence to say where the lines should be drawn, but have in the past been surprised how cheap to run some constantly-enabled heat pumps can be.

A word of warning here. Not all system configurations are that easy to ‘optimise’ for maximum energy-efficiency. The aim is to achieve a low operating water-temperatures and still get adequate heating to the building. If you have a weather-compensation heating-curve, the setting will need engaging with, and hopefully reducing. This should be easy to do, and don’t forget that the response time may be slow. Be mindful that simply reducing TRV radiator valves is not addressing the issue here since the heat pump is not ‘seeing’ the lower water temperature that it likes.

The lowest running costs are likely to be achieved with some amount of night set-back. However, it can be easier, with less risk of setting something wrong, to set the system to constant. You can then find the lowest circulating water temperatures that still keeps you adequately warm. It can be worth experiment. Try it and note down daily electricity use.

The bigger picture

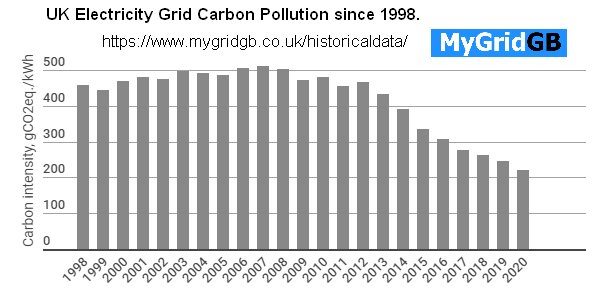

The goal posts in the UK have changed greatly over the last 10 years (say 2010 to 2020). Electricity generation is now twice as ‘green’ and beyond my expectations.

The increase in solar and wind generation, coupled with the phasing down of coal and advent of efficient gas power stations has resulted in the CO2 pollution halving in 10 years. This means that lower COP heat pumps are more acceptable. Added to this, heat pumps have bit-by-bit become more energy-efficient. All-in-all, with a far better selection of energy-efficient products in a now well-established industry, we are far better positioned to install heat pump in all types of building.

Furthermore, there could also some positive advantages for using heat pumps with old ‘heavy’ buildings. The storage of heat in the building’s fabric can mean that we could partly ‘shift’ (in time) the running of the heat pump to coincide with available PV solar, or to benefit from different time tariffs. Future Smart Grids may, in a small way, use the slow-response of old buildings to advantage. We could also ‘incentivise’ and air source system to run at the warmest time of day when its efficiency is high. We are not quite there yet with the necessary ‘intelligent’ controls’ to be able us to control as in these ideas, but it’s coming. I look forward to seeing developments in this area.

4 Comments

Interesting article. We live in a 200 year old stone cottage. We currently heat the house and hot water with 2 wood burning stoves. The house is completely internally insulated with 50mm Kingspan and we are currently installing double glazed windows and doors.

The roof space has 300mm rock wool. It is not possible to install underfloor insulation

With the rise of electricity would we be wise to install a heat pump?

Thanks for the info, very interesting. But can you give us some idea of what sort of heat pump is best? Air or Ground? And which is more cost-effective?

Neil, your old stone cottage should be close to fairly recent spec houses if it has 50mm wall insulation and double glazing, it should be suitable for a heat pump, air or ground source. The rise in electric cost is a concern, and nobody knows how it will pan out. However, most believe that the levy will be shifted from electricity onto fossil fuels. Given the commitments to de-carbonising, it would be hard to believe that heat pumps would be more expensive to run that more conventional alternatives. Given you are fairly well insulated, you should have the opportunity to run radiators at lower and efficient temperatures. I guess you should press potential installers on predicted running costs. They should have easy-to-understand info on your expected future running costs.

Martin,

There is no easy answer for Ground V Air. You should find plenty of discussion about it. The recent winters have been mild, and ASHPs work well if this continues. If we were to get a severe winter, Air Source systems may tend to struggle. Whilst they may work down to -15C or so, their output diminishes in very cold weather… just when the heat demand is highest. ASHPs are much easier and cheaper to install, and if your property is small and/or very well insulated, ASHP might be the most practical choice.

Ground source can be far more expensive to install, and tend to be more energy-efficient in mid winter, especially during a cold snap. How ever the extra cost to install them is not always worth it. GSHPs should last a lot longer that AHPs, and the ground trenches should last an extremely long time. Likewise, most of the rest of the system (e.g. underfloor or radiators for GS or AS) should last a very long time.

Sorry not to give you a definitive answer. I’m guessing that most installers would recommend Air source, and now that the RHI has ended, ground source may be less attractive economically. The final point is noise and location. Not every situation has the right location for an air source system, so each situation needs assessing individually.